THE CHRISTIAN AND THE NON-CHRISTIAN

By Ken Silva pastor-teacher on Aug 17, 2012 in Current Issues, Features

Here we come to a dramatic and almost an abrupt statement. The Apostle has been describing the kind of life which is lived by the “other Gentiles”, the kind of life that these Ephesians Christians themselves used to live – the life still being lived by those of their compatriots and fellows who had not believed the gospel of Jesus Christ. And having finished his description he suddenly turns, and uses this word But. Now to get the full force of this, let us look at the statement again as a whole. “This I say therefore, and testify in the Lord, that ye henceforth walk not as other Gentiles walk, in the vanity of their mind, having the understanding darkened, being alienated from the life of God through the ignorance that is in them, because of the blindness of their heart: who being past feeling have given themselves over unto lasciviousness, to work all uncleanness with greediness. But you have not so learned Christ”; and then Paul goes on to say, “if so be that you have heard him, and have been taught by him, as the truth is in Jesus”.

We come, then, to this extraordinary, dramatic, vivid, almost, I say, abrupt statement which the Apostle makes here. And it is obvious that he put it in this form quite deliberately, in order to call attention to it and to shock them, and in order to bring out the tremendous contrast that he has in mind. And therefore the emphasis must be placed both upon the but and upon the you. “But you” – “you have not so learned Christ”: the you in contrast with those other Gentiles; and the but standing here as a great word of contrast to bring out this marked antithesis. What then do those two words suggest to us?

The first thing, surely, that they should convey to us is a feeling of relief and of thanksgiving. I start with this because I think that it is the thing that we should be conscious of first of all. We have followed the Apostle’s masterly analysis, his psychological dissection of the life of the unbeliever, the pagan, the man who is not a Christian, and we see how it goes from bad to worse because his mind is wrong. He is in a state of darkness, the heart is affected, and he is alienated from God. We have also seen men giving themselves over, in their foulness and lasciviousness, to work all kinds of iniquity and uncleanness with greediness. We have been looking at it all and seeing it. And then, Paul says, “But you”! And at once we say, Well, thank God! we are no longer there, that is not our position. And this, I repeat, is the thing that must come first; we must feel a sense of relief and profound gratitude to God that we are covered by this But, that Paul is here turning from sin to salvation, and that we have experienced the change of which he is now going on to speak.

I emphasize this point because it seems to me that there is no better test of our Christian profession than our reaction to these words “But you”. If we merely hold the truth theoretically in our minds this will not move us at all. If we have looked on at the description of sin merely in a kind of detached, scientific manner, or as the sociologist might do; if we have put down groups and categories of people, and have done it all in an utterly detached way, then we will have no sense of relief and of thanksgiving as we come to these words. But if we realise that all that was true of us; if we realise that we were in the grip and under the dominion of sin; if we realise that we still have to fight against it, then, I say, these words at once give us a sense of marvellous and wonderful relief. It is not the whole truth, of course, there is more to be said. But as we respond to these words, in our feelings, in our sensibilities, as well as with our minds, we are proclaiming whether we are truly Christian or not.

We read these words of Paul, and then we read our newspapers, and as we look at what is going on all around us, we say, Yes, it is absolutely right and true, that is life in this world. And then we suddenly stop and say, Ah! but wait a minute, there is something else 1 – there is the Christian, there is the Christian Church, there is this new humanity that is in Christ! The other seems to be true of almost everybody in the world, but it is not, for “there is yet a remnant according to the election of grace”! Thank God! In the midst of all the darkness there is a glimmer of light. Christianity is a protest in that sense; something has happened, there is an oasis in the desert. Here it is; thank God for it! And therefore I am saying that we test ourselves along these lines. Here we have been travelling in this wilderness, in this desert, and it seems to be endless. There seems nothing to hope for. Suddenly we see it – “But you”! After all, there is a bridgehead from heaven in this world of sin and shame I But you! Relief! Thanksgiving! A sense of hope after all!

The words, “But you”, of course, also mark the entry of the gospel. And I must confess that I am increasingly moved and charmed by the way in which this particular Apostle always brings in his gospel like this. We see him doing it in the fourth verse of his second chapter. He always does it in this way. There we read that terrifying passage in the first three verses, then suddenly, having said it all, Paul says, “But God”! – and in comes his gospel. And he is doing exactly the same thing here. This but, you see, this contrast, this disjunction, this is the Gospel, and it is something altogether different, it has nothing to do with this world and its mind and its outlook; it is something that comes in from above, and it brings with it a marvellous and a wonderful hope.

The Gospel always comes as a contrast. It is not an extension of human philosophy, it is not just a bit of an appendix to the book of life, or merely an addition to something that men have been able to evolve for themselves. No I It is altogether from God, it is from above, it is from heaven, it is supernatural, miraculous, divine. It is this thing which comes in as light into the midst of darkness and hopelessness and unutterable despair. But it does come like that; and thank God, I say again, that it does.

The position we are confronted with is this. We are looking at the modern world in terms of this accurate description of it, and we see that everything that man has ever been able to think of has failed to cope with it. Is political action dealing with the moral situation? Is it dealing even with the international situation? Can education deal with it? Read your newspapers and you have your answer. Hooliganism is not confined to the uneducated. Take all your social agencies, everything man has ever been able to think of. How can it possibly deal with a situation such as that which we have been considering in verses 17, 18 and 19? When you are dealing with a darkened mind, with a hardened heart, with a principle of lasciviousness controlling the most powerful factors in man, all opposed to God, all vile and foul, what is the. value of a little moral talk and uplift? What is the power of any legislation?

You cannot change men’s nature by passing Acts of Parliament, by giving them new houses, or by anything you may do for them. There is only one thing that can meet such a situation; and thank God it can! “I am not ashamed of the gospel of Christ,” says this great Apostle, as he looks forward to a visit to the imperial city of Rome with all its grandeur and its greatness, as well as its sin and its foulness. “I am not ashamed of the gospel of Christ”, he says, and for this reason, “it is the power of God unto salvation”. And because it is the power of God it holds out a hope even for men and women who have given themselves over, abandoned themselves, to the working of all uncleanness with greediness.

I have often said that there is nothing so romantic as the preaching of the gospel. You never know what is going to happen. 1 have this absolute confidence that if the vilest and the blackest character in this city of London today hears this message, even if he is the most abandoned wretch in the foulest gutter, I see a hope for him, because of the gospel, this but that comes in, this power of God! The gospel comes into the midst of despair and hopelessness; it comes in looking at life with a realistic eye. There is nothing, apart from the gospel, that can afford to be realistic; everything else has to try to persuade itself like a kind of self-hypnotism.

Here is the only thing that can look at man as he is, at his very worst and blackest and at his most hopeless, and still address him. Why? Because the power of God is in it. And this is a power that can make men anew and re-fashion them after the image of the Lord Jesus Christ, as the Apostle is about to tell us. It is the work of the Creator. So the Gospel comes in this way, and the words “But you” remind us of the whole thing. (source)

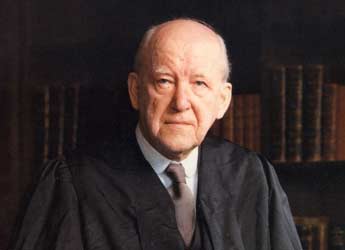

D. Martyn-Lloyd Jones